Understanding Change Data Capture

A tech-agnostic breakdown of the Change-Data-Capture pattern and its popular implementation strategies.

Data pipelining is the work of building stuff that moves data from one place to another over and over again. A common subclass of this type of work involves capturing changes in a structured database, and replicating those changes in some form to another data store. Change Data Capture (CDC) is an architectural pattern within the field of data pipelining that is designed to solve this problem.

In this article, I will go over the different approaches to implementing CDC, their various applications in the real world, and their trade-offs. The final section of this article offers a little challenge for the readers who would like to get their hands dirty.

Push vs Pull Model

CDC solutions can be broadly categorized into two classes. Push model solutions are solutions where the upstream database 'pushes' changes to downstream destinations via some kind of an intermediary broker. The pull model features the opposite pattern where the downstream destinations listen for changes and capture them as they happen.

Push Model Implementations

Trigger Based

Trigger Based CDC is perhaps the most common Push Model implementation of CDC. It looks something like this:

Whenever a change-event (such as an UPDATE) takes places on a specific table or group of tables, a function is triggered. In the case of SQL, this would be a stored procedure.

The function or stored procedure then captures the changes and write them to a data store. This data store may be a destination table or a message bus which alerts downstream sources to capture the changes.

Basic Implementation

Trigger based CDC is simple enough that a very rudimentary version of it can be implemented fairly quickly. Here is a very simple implementation example of Trigger Based CDC using MySQL. In this example, we will log all updates to a simple user table using a trigger-based CDC pipeline implemented with MySQL stored procedures. To keep it simple, we are only setting up a trigger for UPDATE events, but you could extend this example to set up triggers after DELETE, INSERT or other events.

Step 1: Create a Source Table

The following code creates a very simple user table with a user_id as a primary key. We will assume that the user_id column is immutable. This is a practical assumption because primary key columns might be used for joins with other tables and are often designed to be immutable.

CREATE TABLE user (

user_id INT PRIMARY KEY,

name VARCHAR(100),

email VARCHAR(100)

);Step 3: Create a Destination Table

This table will be the destination of your CDC pipeline – in other words, it'll be the table which the stored procedure writes to when capturing changes. In this example, we are maintaining a record of the old and new names and emails, however the schema here could be anything you want. It could also be a 1-to-1 replica of the original table's schema.

CREATE TABLE cdc_user_update_log (

id INT AUTO_INCREMENT PRIMARY KEY,

user_id INT,

old_name VARCHAR(100),

old_email VARCHAR(100),

new_name VARCHAR(100),

new_email VARCHAR(100),

last_modified_time TIMESTAMP DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP

);Step 2: Create a Stored Procedure

This code block creates a stored procedure called cdc_user_update which inserts updates from the source table from Step 1 into the replica table from Step 2. Notice that we are calling NOW() to add a timestamp in the new table's last_modified_time field. Having some kind of a timestamp on CDC tables can be very helpful in more complex CDC systems.

Set the Delimiter

DELIMITER //Create the Procedure

-- We are assuming that the user_id field is immutable for this example.

CREATE PROCEDURE cdc_user_update (

IN used_id_value INT,

IN old_name VARCHAR(100),

IN old_email VARCHAR(100),

IN new_name VARCHAR(100),

IN new_email VARCHAR(100)

)

-- Add your CDC logic here

BEGIN

INSERT INTO cdc_user_update_log (

user_id,

old_name,

old_email,

new_name,

new_email,

last_modified_time

)

VALUES (

used_id_value,

old_name,

old_email,

new_name,

new_email,

NOW()

);

END//Reset the Delimiter

DELIMITER ;Step 3: Create a Trigger

Finally, we create a trigger which runs the stored procedure from the previous step every time there is an update event on our source table.

Set the Delimiter

DELIMITER //Create the Trigger

CREATE TRIGGER user_after_update

AFTER UPDATE ON user

FOR EACH ROW

BEGIN

-- Call the stored procedure for each update

CALL cdc_user_update(OLD.user_id, OLD.name, OLD.email, NEW.name, NEW.email);

END;Reset the Delimiter

DELIMITER;Step 4: Test the Trigger

Check the cdc_user_update_log table (it should be empty):

SELECT * FROM cdc_user_update_log;Insert a user and update it (remember that we only implemented a trigger for updates, not inserts):

INSERT INTO user(user_id, name, email) VALUES(1,'Prateek S', 'Prateek.S@fakemail.com')

UPDATE USER SET name = 'Prateek Sanyal' WHERE id=1;Check the cdc_user_update_log table again. It should have a row with the old and new email, and a last_modified_time field.:

SELECT * FROM cdc_user_update_log;Pros of Trigger Based CDC

Easy to Implement: Most databases offer some kind of triggers or hooks on write operations. This makes trigger based CDC quick and easy to implement. There is no need for any tools external to the Database itself. There is also no need to set up a scheduler or event bus like in the Push Model Implementations.

Real-Time: Whereas building real time CDC in Pull Model implementations requires careful consideration, trigger based CDC is real time by default. There is no need to manage streaming watermarks or any other complexities related to real time stream processing systems.

Granular Control: Triggering the logic for CDC on row-level changes allows for granular control and reduces the risk of losing or misrepresenting changes – a risk that is particularly high with the Polling/Query based model explained later in this article.

Cons of Trigger Based CDC

Hard to Orchestrate: A major challenge with this model is that it can be hard to orchestrate the CDC system since it is tightly coupled with the database itself. What happens if the destination database needs to be repopulated with a re-run of the CDC pipeline? There is no easy way to achieve this. Furthermore, the development of a centralized dashboard to track metadata about stored procedure runs and triggers may need to be developed outside of the DB in a real-world application. The same features that make trigger-based CDC so easy to implement also make it hard to manage.

Schema Evolution Challenges: A lot of modern log-based CDC tools offer schema inference capabilities and are able to handle schema evolution automatically. In the case of trigger-based CDC implemented using stored procedures and triggers, this can be challenging because data types are manually configured on the destination tables. There is a general lack of flexibility with this approach which makes schema evolution handling harder.

Scalability Challenges: Perhaps one of the biggest challenges with this approach is that the compute resources required for CDC are coupled with the Database itself. Under high loads of write operations, the triggers may bottleneck the system and affect the database’s performance. It may not be possible to scale the CDC system independently from the database, making it unsuitable for large scale systems.

Pull Model Implementations

Polling/Query Based

Polling or Query based CDC involves running a data pipeline on a schedule that can poll the source data sources for changes and subsequently copy those changes to the destination. A simple implementation of this pattern is as follows:

A pipeline orchestrator (like Airflow) schedules a pipeline to run specific queries against a source database. In a SQL DB, these would just be

SELECTqueries on the source DB, with a filter to start reading from the earliest row proceeding the last-modified timestamp that has already been captured in the destination DB.The pipeline then applies any required transformations on the data, and loads it to the destination table, with an added timestamp marking when the data was captured.

Additional queries may be added to track total row counts if the system needs to identify deletes. In this pattern, tracking delete transactions can get very complicated to implement, but calculating the number of rows delete is slightly less complicated.

This pattern for CDC directly applies the most general data pipelining pattern for batch-processing ETL jobs. It isn’t designed specifically for the CDC problem and has a lot of drawbacks compared to the other options (discussed in the ‘Cons’ section below). For this reason, it is rarely used in real-world CDC frameworks designed for large-scale systems.

Pros of Polling/Query Based CDC

Easy to Implement: The main advantage of this pattern is that it is very easy to implement for a quick and lean solution. It is a simple way of capturing changes on a schedule, especially when a comprehensive record of transactions is not important.

CDC can Scale Independently of Databases: Similar to other Pull Model implementations (like log-based CDC discussed in the next section), the CDC framework and its orchestration is separated from the Database, allowing them to scale and be managed independently.

Cons of Polling/Query Based CDC

Potentially Missed Transactions: If there is are multiple changes in state between two scheduled polls that cancel each other out, the downstream destination will not be aware of those transactions, except any updates to a last-modified timestamp.

Source Table Requires Last Modified Timestamp: Some kind of a last-modified timestamp is required for the polling query to know which changes to capture, otherwise it would have to diff the destination and source table each time.

Complexity of Tracking Deletes: Identify deletes is much more complicated. The system will have to do so by comparing the delta of the source and destination tables which can be an expensive operation at large scales.

No Transaction Record or History Replayability: There is no easy way to replay history since there is no record of changes available. If changes between each poll run are tracked somewhere, this may be used to create a snapshot history, but it requires a lot of additional software design as compared to using the native transaction log of a DB. Replaying history can be essential to backfill a CDC pipeline in case of errors.

Log Based

Log Based CDC has become one of the most common CDC patterns for real-world applications. This type of CDC implementation requires the source data store to have a transaction log that can be used to replay the history of state changes to every dataset. This type of log is usually a native feature of all major databases. The list below contains the corresponding transaction logs for some of the major open sources databases:

MySQL: Binary Log (BinLog)

PostgreSQL: Write Ahead Log (WAL)

MongoDB: OpLog

SQLite: Write Ahead Log (WAL)

MariaDB: Binary Log (BinLog)

Let's consider a basic example to understand the flow of log-based CDC. In this example, we will consider what happens when an UPDATE/INSERT/DELETE Query is sent to a SQL DB, and a log-based CDC application is listening downstream to send the changes to multiple destination data stores.

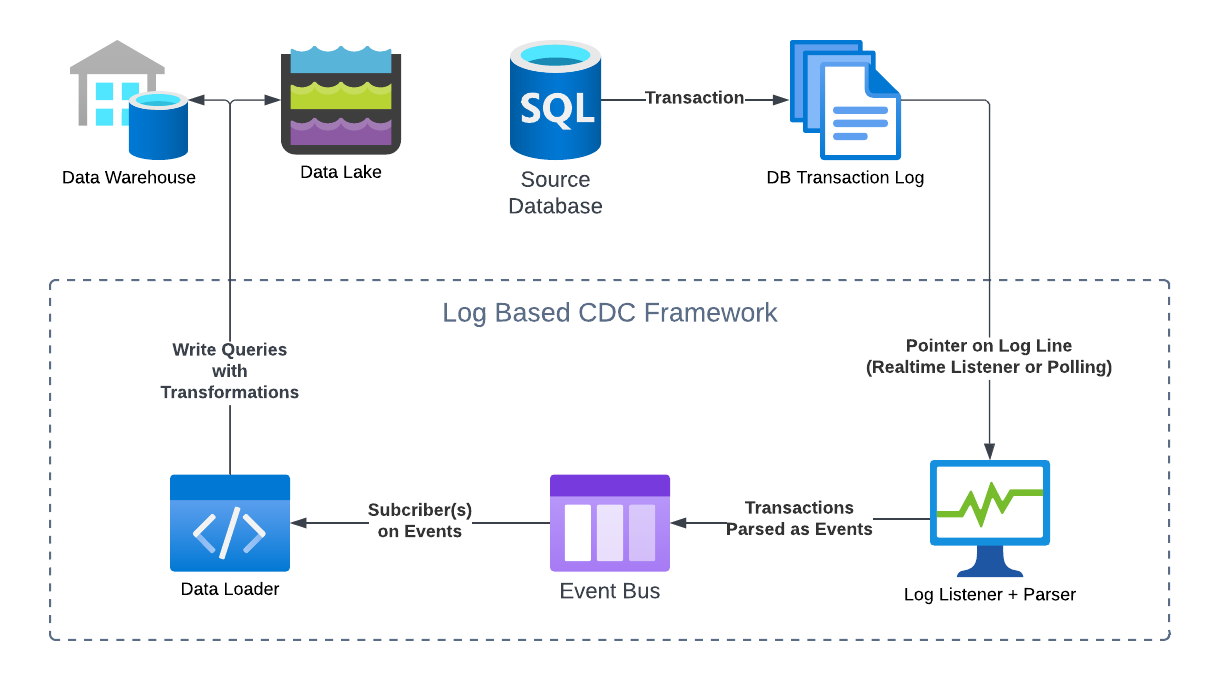

The Source DB receives the query and runs it. This also updates its transaction log.

The CDC application is listening to the transaction log. It maintains a pointer to the last record it updated from the log, so if there are any records after the last updated location, the listener iterates over the updated records and sends the updates downstream to an event bus while moving the pointer simultaneously. This can be done in real-time or in micro-batches via polling, since in both cases, the pointer on the logs ensures the listener starts reading from the right record. In this case, the query the source DB ran would have generated at least one transaction log, which the listener will parse and send to the event bus as one or more events.

The downstream event bus acts as a publish-subscribe service, which receives events and stores them for downstream subscribers. The events it received are composed directly from the transaction record and contain instructions that downstream data sources can use to replay the changes.

Finally, one or more data loaders will receive these events based on predefined subscribers. They will convert the events into queries that will write the changes to the destination databases. At this step, the CDC framework may allow for additional transformations to be applied.

The Diagram below explains roughly how this works:

The exact terminology and architecture will differ from framework to framework, but the general flow should remain more or less the same for all log-based CDC systems.

Pros of Log Based CDC

Highly Scalable: A major reason why this model is favoured by CDC-as-a-Service vendors is because of its highly scalable nature. The CDC process is completely decoupled from the source and destination databases. When using an intermediary event bus like Kafka, the framework is able to auto scale horizontally to handle spikes in transactions while having very little impact on the source database.

Minimal Impact on Source Databases: As a continuation of the scalability factor, Log Based CDC frameworks do not directly read any tables except the transaction log. They also do not use up additional workers on the source database to execute a CDC pipeline. The resource footprint on the source systems is relatively low. A single persistent connection to the transaction log is usually enough.

Lossless Change Tracking and History Replayability: A feature of a databases’ transaction log is that tracks every single transaction on a database, and a well designed Log-Based CDC will therefore have access to a comprehensive history of everything that has happened on the source system. In theory, it is possible to build a log-based CDC system that can comprehensively replay the history of changes on a source database without missing a single change. Neither of the previous two CDC patterns can achieve this outcome.

Fault Tolerance and Resilience: An advantage of using the transaction log as a source of truth and decoupling the CDC pipelines from the source database is that recovering from system failures is easier. If a pipeline breaks down, or the event bus crashes, it should be possible to reload all lost or corrupted events from the transaction log.

Cons of Log Based CDC

Difficult to Implement: Implementing log based CDC properly requires overcoming some complex initial challenges. While the full list of challenges may be too many to count, the following are some significant considerations:

A parser needs to be implemented that can parse transactions from the log into meaningful events, without missing any important transaction details.

An pub-sub style event system needs to be implemented using technologies like Kafka which are notoriously high-maintenance.

A pointer to the correct index in the log file needs to be maintained at all times, which may need to be moved precisely for retries.

Multiple event subscribers need to be managed using a centralized orchestrator, all of which requires deliberate planning.

A DB Log is Required: While this goes without saying, it is essential for the source database(s) to have a native transaction log. This is not an issue for most SQL and some NoSQL Databases. However, it can become a challenge if the source system is a Data Lake or some other type of non-relational data store without a comprehensive transaction log.

Managing Data Staleness and Freshness Guarantees: Since Log Based CDC often relies on multiple moving parts – a log reader, parser, event bus etc., it becomes harder to accurately anticipate the latency of the CDC process. In other words, it is hard to know exactly how stale the data in the destination system is, and what type of freshness guarantee SLAs the destination system can offer. This is a practical problem experienced by real-world vendors of log-based CDC. A common manifestation of this problem is when there is a spike in transactions in the source system, the event pipeline may experience higher latencies in processing the transaction events, which would lead to higher latencies in the downstream destinations. While the destination tables can be explicitly aware of how far behind they are lagging (using last-modified timestamps), it is hard to estimate the upper bounds of this lag.

Real World Context

As of today, the most common pattern we see in large-scale CDC frameworks is the Log Based CDC pattern. Debezium stands as the most popular open source framework implementing this pattern. Debezium is designed to interface with SQL source databases like MySQL and Postgres, and uses Kafka as its event bus. Various 3rd party vendors have emulated this model and extended Debezium’s architecture.

As of today, the frontiers of innovation in the CDC ecosystem involve:

Log-Based CDC with non-relational data sources like data lakes. Innovations like the Delta Lake framework and Iceberg tables have made it possible for data lakes to have ACID transactions like a more traditional database. This also means that it is now possible to have data lakes with transaction logs. This space is evolving quickly as the major vendors of CDC technology compete to support data lake sources.

Cost Attribution and Budgeting for CDC Pipelines. Due to the highly scalable nature of log-based CDC systems, managing costs is an important aspect for users. A key challenge is to be able to correctly attribute the cost incurred by every table’s pipeline (including the events it generates), and ensure they stay within budget.

Managing Lag and Data Freshness. As explained earlier, log-based CDC has an inherent limitation of a difficult-to-predict lag between changes in the source databases and the destination. A lot of cutting-edge research is focused on minimizing this lag and making it more predictable. It stands to become a key differentiator for CDC vendors.

Reader Challenge

If this article has inspired you to dig deeper and get your hands dirty. Try this:

Set up a MySQL Database locally.

Install Maxwell’s Daemon a lightweight and opensource CDC tool that connects to and reads the MySQL binlog, and sends events to a downstream event bus.

Set up Apache Kafka locally.

Download the MySQL ‘Employees’ sample database and load it into your local MySQL.

Connect Maxwell to your MySQL DB as a source, and use it to pipe all changes to Kafka.

Use ksqlDB to query the transaction data from Kafka and explore it.

NOTE: Remember to turn off all the processes after you’re done. If you prefer a Dockerized environment, there are Docker images available for MySQL, Maxwell, and Kafka.